The Boswell Sisters’ house

3937 Camp StreetNew Orleans LA 70115

The Boswell Sisters—Martha, Connie, and Vet—were the most popular vocal group in America in the early 1930s. Though their career was relatively brief, their pioneering music, shaped by the sounds of their New Orleans childhood, proved profoundly influential.

Frank Sinatra called Connie Boswell, whose solo career continued through the 1960s, “the most widely imitated singer of all time,” and Ella Fitzgerald said she was the “only…singer who influenced me.”

The Boswells were born into a musical, middle-class family that moved to New Orleans in 1914, when they were nine, seven, and three years old. As children they played classical instrumental music under Professor Otto Finck, a renowned teacher who would later teach the first generation of the city’s rhythm and blues artists at the Grunewald School of Music. The sisters’ talent was evident early on—Connie and Vet performed at the famed French Opera House as schoolchildren in 1919, just months before it was destroyed by fire.

In the 1920s the Boswell house became a hive of activity for young white jazz musicians including future star Louis Prima and his brother Leon; cornet virtuoso Emmett Hardy, who reputedly bested a young Louis Armstrong in a cutting contest but died at 22 (breaking Martha Boswell’s heart); and clarinetist Pinky Vidacovich, uncle of master drummer Johnny Vidacovich.

While their social milieu was segregated, the Boswell sisters listened eagerly to Black artists, including Armstrong’s groundbreaking records and performances by Mamie Smith, Bessie Smith, and other vaudeville legends at the Lyric Theater. They even parked outside of Black churches to listen to gospel music. Early in their recording and radio career, some audiences assumed the sisters were African American or Afro Creole. (While they largely avoided minstrelsy, in the late 20s Martha appeared in a radio variety show as a “sassy” Black character.)

The sisters drew on the swing of Black New Orleans music in their vocal arrangements, which they crafted together by ear. Drawing on their shared training and close bond, they developed complex harmonies and seamless modulations of key and tempo without written compositions. Their sound was playful, like the sisters themselves (Connie, who lost the use of her legs as a child, built enough strength in her arms to win a game of hide-and-seek by hanging out of a second floor window of this house).

The trio’s first break came at a vaudeville show at the Orpheum Theater in 1925, when a headliner’s cancelation gave them top billing as “New Orleans Princesses of Harmony.” Soon they were appearing on the radio and touring the South. According to author Kyla Titus, granddaughter of Vet Boswell, they couldn’t afford a wheelchair, so Martha and Vet carried Connie by making “what they called a ‘packsaddle’ by crossing their forearms and clasping each other’s wrists.”

The Road to Stardom

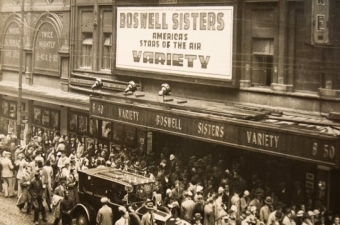

In 1928 the sisters followed the vaudeville circuit out of New Orleans, landing in California before stepping up to New York in 1931. There they became favorites on national radio broadcasts, a format that suited their ability to share a single microphone. In July of that year, they sang on the first ever television broadcast to include sound. Louisiana governor Huey Long named them “Ambassadors of Harmony.”

In New York studios, they crafted arrangements for musicians including Glen Miller, Benny Goodman, and Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, who, shortly afterward, would use a similar feel in their work as blockbuster bandleaders of the swing era. The sisters’ joyful, lighthearted sound became a sensation as the country struggled to bear the weight of the Great Depression.

Martha, Connie, and Vet became celebrities, appearing in films and touring Europe. At home, newspapermen filled columns with rumors about their potential romances. They notched 19 top-20 hits, including the number one smash “The Object of My Affection” in 1935.

In 1936, though, the Boswell Sisters’ days as a trio came to an abrupt end. Many accounts then and since attributed this to their choices to marry and have children, but Titus’ The Boswell Legacy, informed by the family’s private archive, suggests that the group was mismanaged and limited by Connie’s ambition as a solo artist.

Connie went on to score a number of solo hits in the 1940s and 50s, and often performed duets with Bing Crosby, whose syndicated radio show had helped launch the Boswell Sisters to prominence (she changed the spelling of her name to Connee to speed the signing of autographs). It was a remarkable run for a woman who’d been denied opportunities for years due to her disability.

Despite spawning close-harmony imitators including the Andrews Sisters (of “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” fame), the Boswell Sisters faded from the popular imagination over the ensuing decades, and their place in the history of New Orleans music was often overlooked. However, in 2014, 100 years after the Boswell family came to town, a major exhibition, documentary, and book helped revive an appreciation for their work.

Videos

The Boswell Sisters perform "Heebie Jeebies," one of their signature arrangements.

Video posted by mrhokum.

The Boswell Sisters perform "Heebie Jeebies," one of their signature arrangements.

The Boswell Sisters perform "Crazy People," showing off their swing.

Video posted by Olivier Cotton.

The Boswell Sisters perform "Crazy People," showing off their swing.

The Boswell Sisters promote agricultural production in "Close Farm-ony."

Excerpt from the documentary "The Boswell Sisters: Close Harmony."

Video posted by Joshua Tree Productions.

Excerpt from the documentary "The Boswell Sisters: Close Harmony."