The Brass Rail

1316 Canal StreetNew Orleans LA 70112

From the moment prohibition ended in 1933 until the vice squad padlocked it in 1962, the Brass Rail anchored a cluster of clubs on the 1300 and 1400 blocks on Canal Street that functioned as an extension of French Quarter nightlife. Its place in New Orleans music history comes courtesy of bandleader and producer Paul Gayten, a major figure in rhythm and blues, who was headquartered here from 1952 to 1958.

Gayten was a veteran pianist and singer who’d influenced Dave Bartholomew and others in the 1940s, when R&B was emerging in Black clubs like the Robin Hood—he recorded “True,” considered New Orleans’ first R&B hit, in 1947. For the white-only crowd at the Brass Rail, Gayten also interpreted mainstream pop hits of the day. His house band featured some of the city’s best players, including, at various points, saxophonist Lee Allen, bassists “Chuck” Badie and Frank Fields, and drummers Earl Palmer and Charles “Hungry” Williams—musicians earning national reputations for the hit records they cut in nearby J&M Studio.

The Brass Rail was a happening club. Gayten’s residency coincided with a renovation that installed “a unique, modern eighteen-foot stage recessed in the semi-circular bar,” crowned by a “canopy dome.” There was a modern edge to the entertainment, too: Badie told A Closer Walk that a gig of his at the Brass Rail was the first appearance of an electric bass on a New Orleans stage (the club’s manager barked at the band for using two guitars before Gayten enlightened him.)

Before he became famous as Dr. John, 12-year-old Mac Rebennack used to skip mass on Sunday mornings and take a streetcar to the Brass Rail, where, inside, it was still Saturday night. Gayten presided over after-hours cutting contests, and Rebennack finagled his way in to see soon-to-be legendary horn men like Sam Butera and Lee Allen blow each other away. In his memoir Rebennack recalled, “The whole scene was so sweet it was almost sugar diabetes, and I just couldn’t get enough of it.”

Rebennack went on: “Paul [Gayten] was so progressive—and tough—about his views of race. He was instrumental in breaking up the strict color line that prevailed at that time in the clubs and recording studios in New Orleans.” Segregation was enforced by the police and backed by the musicians’ union, but Gayten defied them to set up gigs with Black bands for Butera and, before long, Rebennack. It was a privilege unavailable to Black artists looking to break in with white groups.

Gayten also helped launch Bobby Charles, a Cajun teenager from Abbeville, Louisiana, who became a revered songwriter. In 1955 Chess Records in Chicago had signed Charles thinking he was Black—he auditioned over the phone with a song he wrote, “See You Later, Alligator.” Gayten was an A&R man for Chess, helping the label cultivate talent around New Orleans. He used the stage at the Brass Rail to groom Charles, and produced many of the youngster’s records. “I was father and mother to him,” Gayten said later. (The paternalism extended to Charles’ paycheck, as Gayten took co-writing credits on a number of songs.)

Accompanying Charles on some trips from Abbeville to the Brass Rail was his friend Warren Schexnider, another aspiring musician. He picked up Charles “Hungry” Williams’ drumming style—“a heavy foot and a lot of cymbals”—and took it back to Cajun country, where, as Warren Storm, he became a founding father of swamp pop, a South Louisiana subgenre built on R&B drumbeats and piano triplets.

In 1956 Gayten broke another teenager, Clarence Henry, who’d been a student of his wife’s at L.B. Landry High School on the Westbank. Gayten had label head Leonard Chess fly down to see Henry perform with his band at the Brass Rail. Chess liked what he heard and sent Henry and Gayten to Cosimo Recording Studios—the brand-new successor to J&M—where he cut the classic “Ain’t Got No Home,” with Henry singing “like a girl” and, inimitably, “like a frog.” He embarked on a storied career as Clarence “Frogman” Henry, which included a hit, “But I Do,” penned by Bobby Charles.

As author Jeff Hannusch records, Gayten’s success with these artists landed him a job in Los Angeles, expanding Chess Records’ operation on the West Coast. In his absence, the Brass Rail hired forgettable bands and turned to strip-tease acts on the recessed stage to siphon business from nearby Bourbon Street.

The club had reputed ties to the New Orleans underworld, and had attracted attention from law enforcement going back to the 30s, when raids turned up illegal gambling operations. In 1961 the Brass Rail became a target of District Attorney Jim Garrison’s vice crackdown, and was shut down for good the following year.

Videos

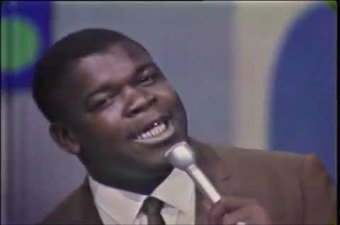

From the enthusiastically titled TV show The !!! Beat in 1966, Clarence "Frogman" Henry sings his signature hit, "Ain't Got No Home," which he recorded following a showcase at the Brass Rail.

Video posted by Bobby Gass 5.

From the enthusiastically titled TV show The !!! Beat in 1966, Clarence "Frogman" Henry sings his signature hit, "Ain't Got No Home," which he recorded following a showcase at the Brass Rail.

Rare footage of Bobby Charles and Mac Rebennack (aka Dr. John) performing "Down South in New Orleans" with The Band in 1976. Charles broke into the industry at the Brass Rail, and Rebennack started sneaking into the club when he was 12.

Video posted by dolfkoeienverhuur

.

Rare footage of Bobby Charles and Mac Rebennack (aka Dr. John) performing "Down South in New Orleans" with The Band in 1976. Charles broke into the industry at the Brass Rail, and Rebennack started sneaking into the club when he was 12.

The first of several performances by Warren Storm recorded for a Lafayette TV show in 1981. He studied the big beat of New Orleans R&B at the Brass Rail and brought it back to Cajun country.

Video posted by Warren Storm, Willie T, and Cypress KADN TV.

The first of several performances by Warren Storm recorded for a Lafayette TV show in 1981. He studied the big beat of New Orleans R&B at the Brass Rail and brought it back to Cajun country.

Images