Mardi Gras Lounge

333 BourbonNew Orleans LA 70130

Jimmy King’s Mardi Gras Lounge opened on the ground floor of this townhouse in 1946 (the proprietor, Jimmy King Anselmo, was the father of Louisiana Music Hall of Fame inductee Jimmy Anselmo, who would open Jimmy’s Music Club uptown in 1978). Behind the bar, the bandstand featured a tableau of smiling jesters.

In addition to burlesque dancers like the tassel-spinning Baby Dumplin’, the Lounge presented top-shelf traditional jazz bandleaders such as Oscar “Papa” Celestin, George Lewis, and Freddie Kohlman. Brothers Percy and Willie Humphrey played here, too, before joining the first generation of Preservation Hall bands in the early 1960s. Singers Lizzie Miles and Blanche Thomas, with her rich, bluesy voice, were regulars as well.

Around 1953 clarinetist Sid Davilla, who was Italian, bought the Mardi Gras Lounge and sat in with the Black musicians he hired, defying the segregation laws of the day. Burlesque dancers such as Wild Cherry continued to be part of a night’s entertainment, which went late into the night.

As rhythm and blues crossed over to white audiences, the lineup at the lounge diversified. Author John Broven noted that guitarist Roy Montrell performed here in a trio called the Little Hawketts. Montrell became an in-demand R&B player, joining Allen Toussaint‘s house band and Harold Battiste’s All For One group. He went on to be Fats Domino’s bandleader.

By the late 50s, bowing to pressure from the tourist market, live music at the Mardi Gras Lounge gave way to strip-tease acts. NBC news anchor David Brinkley filmed a segment with Davilla about this change in 1962, dismayed that these shows “had an appeal that jazz somehow is unable to match.” The bar operating here today is named after its most popular attraction: Huge Ass Beers.

About Bourbon Street

Bourbon Street, one of the most famous streets in the country, is only 14 blocks long, running through the middle of the French Quarter. It took off as an entertainment district in the 1940s, when wartime activity brought waves of visitors to New Orleans. Bands often performed in floor shows featuring burlesque dancers (who stripped to varying degrees), comedians, and other entertainers.

This freewheeling era came to a close, in the eyes of many patrons, with District Attorney Jim Garrison’s vice raids in the early 1960s. Crime — organized and not — was pervasive on Bourbon Street, and Garrison’s crusade scored some political points. The resulting loss of revenue at the clubs, meanwhile, scaled back entertainment budgets.

The only Black people on Bourbon Street at the time were there to work (musicians were generally considered hired help; some had to wait in storerooms between sets). Even after the passage of civil rights legislation some clubs resisted desegregation, and audiences on Bourbon Street remained largely white for years afterward.

In recent decades, as the city relied increasingly on tourism to prop up its economy, the market dictated more changes: Modern stripping supplanted burlesque and DJ booths replaced bandstands. The street became a pedestrian mall, filled with go-cups and Mardi Gras beads year-round. Several clubs sticking with live music offered low wages for bands to play songs familiar to visitors.

Hand-wringing about the quality and nature of live music on the strip has been more or less constant since the 1950s, and not without reason. Still, some venues persisted in hiring reputable artists. In the 2000s, the To Be Continued Brass Band took matters into their own hands, breaking into the scene by playing on the corner of Bourbon and Canal Street every night.

In any case, millions of visitors to the strip each year find the spectacle they’re looking for, exotic but approachable, with a more permissive atmosphere than they feel at home. Its economic impact on the city is in the billions. If it’s crass it’s also egalitarian: Bourbon Street today is among the more integrated spaces in town.

Videos

Clarinetist George Lewis performs his signature tune, "Burgundy Street Blues."

Video posted by Konrad Klingelfuss.

Clarinetist George Lewis performs his signature tune, "Burgundy Street Blues."

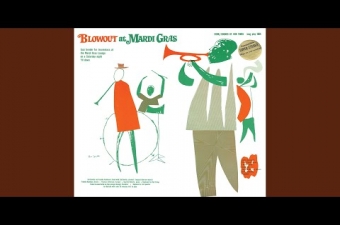

Mardi Gras Lounge proprietor Sid Davila and Freddie Kohlman perform "Three- Thirty-Three" a tune named for the club's Bourbon Street address.

Provided to YouTube by Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Mardi Gras Lounge proprietor Sid Davila and Freddie Kohlman perform "Three- Thirty-Three" a tune named for the club's Bourbon Street address.

Images