Danny and Blue Lu Barker’s House

1277 Sere StreetNew Orleans LA 70122

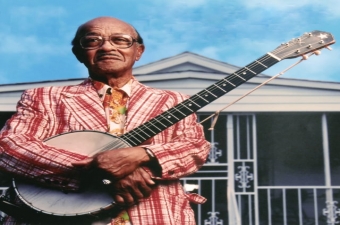

In 1965, the banjoist and guitarist Danny Barker (1909-1994) and the singer Blue Lu Barker (1913-1998) moved into a modest house here, not far from where they grew up. They’d spent the previous 35 years in New York, where Mr. Barker played with some of the biggest names in jazz. Their homecoming would profoundly affect the city’s music community at the end of the 20th century.

Mr. Barker’s family, the Barbarins, included some of New Orleans’ finest musicians: his grandfather Isidore was in the great Onward Brass Band and his uncle Paul played drums with Louis Armstrong and other luminaries. Mr. Barker first earned money as a musician by forming a spasm band – a group of kids busking with simple instruments. He was playing the banjo professionally by 15, and gigging in dance halls and honky tonks all over town.

In 1930 the Barkers married and left the Jim Crow South for Harlem. Mr. Barker quickly found work there with Jelly Roll Morton (they came from the same Seventh Ward creole community—Morton called Barker “Home Town”). Mr. Barker’s sense of rhythm and reputation for playing “big fat chords” on guitar earned him tour dates and session work with artists from Lucky Millinder to Willie “The Lion” Smith.

As her stage named indicated, Louisa Barker sang the blues. She also worked blue, recording a number of risqué songs written by her husband (who once remarked that jazz was about “belly buttons hitting next to one another.”) Mrs. Barker’s most popular number was “Don’t You Feel My Leg,” released as “Don’t You Make Me High” in 1938.

When Cab Calloway heard the couple perform the song, he hired Mr. Barker to play guitar in his orchestra. Barker spent the next eight years playing packed theaters across the country while Mrs. Barker stayed at home with their daughter. One of his bandmates, Dizzy Gillespie, introduced Mr. Barker to Charlie Parker, with whom he recorded in 1945.

When the Barkers moved back to the Seventh Ward, they continued to perform and record. Mr. Barker also embarked on a remarkable third act as a historian, mentor, and what would later be termed a tradition bearer—a sharer of the lore and customs of the early days of jazz.

Mr. Barker had always solicited stories from elder musicians and recorded the names of artists who might otherwise be lost to memory. Fittingly, he became a curator at the New Orleans Jazz Museum (a predecessor of the current institution by that name). Not content to leave jazz history writing to outsiders, he published his own work, including an excellent memoir.

Most consequentially, Mr. Barker apprenticed scores of young musicians who developed into influential bandleaders and artists. The best-known bunch was the Fairview Baptist Church Christian Marching Band, which reinvigorated the parading tradition he grew up with, and led to the city’s brass band renaissance in the 1980s and 90s. Barker instilled in his acolytes (and audiences) an appreciation of Black New Orleans culture that has reached further into the mainstream in the years since his passing. Today, he is widely revered for promoting the continuity of that culture across multiple generations.

Videos

From 1990, Danny Barker performs his inimitable version of "St. James Infirmary" at the Newport Jazz Festival.

Video posted by Jazz on MV.

From 1990, Danny Barker performs his inimitable version of "St. James Infirmary" at the Newport Jazz Festival.

An appreciation of Danny Barker's musicianship, from WWOZ's Tricentennial Music Moments.

Video by WWOZ.

An appreciation of Danny Barker's musicianship, from WWOZ's Tricentennial Music Moments.

Extended performances and an interview with Danny Barker ca. 1990.

Video posted by Bob and Ruth Byler Archival Jazz Videos.

Extended performances and an interview with Danny Barker ca. 1990.

Images