Walter L. Cohen High School

3620 Dryades StreetNew Orleans LA 70115

Drawing from a deep well of talent in Uptown New Orleans, Walter L. Cohen High School produced generations of star musicians, from Huey “Piano” Smith to Big Freedia. The school’s band programs shined from the 1950s through the 1970s thanks to Professor Solomon Spencer, also called Fess, a behind-the-scenes force in New Orleans music. In the 1980s and 90s, some of the city’s biggest figures in hip hop continued the school’s musical legacy.

Huey Smith was among Cohen’s earliest cohorts of students. As a teenager in the early 1950s, he was already impressing older musicians with his piano skills. As biographer John Wirt wrote:

Guitar Slim would go looking for Huey at Walter L. Cohen High School. “A man out there and he looking for Huey,” a boy shouted one day when Slim arrived. Slim’s appearance, including orange hair and pant legs of contrasting bright colors, tickled the students. They crowded the school’s windows, laughing at the man outside who resembled a clown. But Slim had something serious on his mind. “Come on, boy,” he told Huey. “The man at the Tiajuana want us to play on intermission.”

When intermissions at Club Tiajuana turned into a steady gig in the house band, Smith left Cohen to pursue a career in music, which soon took him to J&M Studio, and from there to the Billboard charts.

Solomon Spencer in the R&B era

Presiding over Cohen’s concert band and marching band, Solomon Spencer taught a number of students who became successful rhythm and blues musicians (Spencer himself, according to guitarist and bandleader “Deacon” John Moore, performed with Ray Charles).

Spencer provided the only formal music instruction the acclaimed drummer Idris Muhammad ever had. Muhammad, named Leo Morris at the time, was already backing stars like Big Joe Turner in Art Neville’s Hawketts while attending Cohen, and would soon go on the road with Sam Cooke. Spencer ensured that Muhammad, and countless others, learned to read music by removing any student from the band who didn’t keep up.

Saxophonist Julius Lewis, best remembered for his work in brass bands like the Pinstripe, played in an R&B group called Sound Corporation while at Cohen in the 1960s. In the essential book Talk That Music Talk, Lewis recounted Spencer’s teaching style:

His arrangements were so fast. We wouldn’t even get a sheet of music. He’d do it on the board. “This your part, this your part, this your note. Now, let’s go.” He was also an excellent alto saxophone player. Sometimes he just would stand in front of the class and start wailing.

In OffBeat, Deacon John credited Spencer with supporting the professional ambitions of young musicians, using his status to give them entrée at white institutions during segregation:

How we got on the frat circuit was through a guy called Solomon Spencer. He was the entertainment director at Lincoln Beach and the band director at Cohen High. He booked us weekends at Lincoln Beach but he also booked the fraternity houses, and he booked Valencia, which introduced me to the higher echelon of New Orleans society. Spencer had a lot of bands. Spencer drove a Studebaker we called ‘the whirly bird.’ He’d pick up one band at 5 o’clock and then drop them off at their gig. Then he’d go get another band and drop them off. Some nights he’d have four or five bands working and he’d pick ’em all up at the end of the night and bring them home. He really got a lot of careers in New Orleans off the ground.

Cohen student and future star vocalist Aaron Neville, who sang doo-wop in the school bathroom because it had good acoustics, had a different take on the arrangement:

Solomon Spencer put together a couple of bands made up of students, all of them called the Avalons…Leo [Idris Muhammad] was the drummer, and he recommended me. That teacher was making good money off those bands, but he was the only one who was. We made about twenty dollars a gig.

In any case, Spencer remained a fixture at Cohen from the classic R&B period through later generations of soul and funk.

A partial round-up of Cohen students in and around the Neville family suggests the extent of Spencer’s influence among Uptown musicians: they included Aaron Neville’s younger neighbor, the vocalist Phillip Manuel; Neville neighbors and in-laws Ricky and Norman Caesar of the Caesar Brothers Funk Box; Neville Brothers bassist Rodger Poche; Aaron’s son Ivan, a solo artist and leader of Dumpstaphunk; and Ivan Neville’s bandmate, the bassist Nick Daniels.

Soul singer “Brother Tyrone” Pollard went to Cohen, too, as did bluesman Mem Shannon, who studied clarinet and guitar under Spencer.

Solomon Spencer and traditional jazz

Spencer was equally influential in jazz and brass band music. In Talk That Music Talk, bandleader Gregg Stafford remembered Spencer tapping him on the shoulder when, as a freshman at Cohen, Stafford was debating which elective to take:

[Spencer] said, “Open your mouth and grit your teeth.”

I’m looking at him.

“Just do what I say.”

I gritted my teeth.

He said, “Take instrumental music.”

The band’s trumpet players were due to graduate, and Spencer needed new recruits with suitable chops. Stafford was interested in tenor sax, but Spencer said that wasn’t up to him, and gave the youngster a cornet. According to Stafford:

It was green, tarnished, and banged up…. And it smelled bad. My band director said, “I’m going to give you some polish. You are going to clean this up, and you are going to use this horn.”

After learning the basics, Stafford made the Cohen band as a trumpeter, and when he played the Tulane University homecoming parade, he met some guys affiliated with the E. Gibson Brass Band. They tapped him to play an Elks Parade—his first gig, around 1969. That readied him to join Danny Barker’s Fairview Baptist Church Band in 1972, which set him on a path to become a standard bearer for traditional jazz.

Herbert McCarver III, future leader of the Pinstripe Brass Band, went through Spencer’s program, as did future members of the Preservation Hall Jazz Band including trombonists Maynard Chatters and Freddie Lonzo.

Spencer also helped prepare Stanton Davis to get into Boston’s prestigious Berklee College of Music, after which Davis cut the seminal jazz/funk fusion album Brighter Days.

Solomon Spencer’s background and legacy

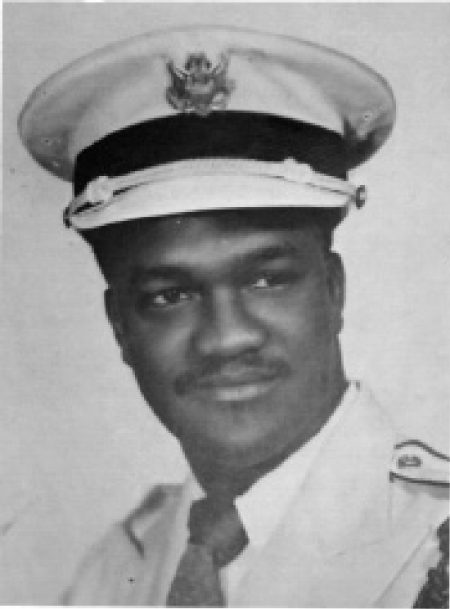

According to Idris Muhammad, Spencer was “one of the first two black cats in the United States Navy Band.” In New Orleans, he played in William Houston’s Big Band, one of the city’s finest ensembles of the big band era, which was stacked with music teachers.

As a member of the B-Sharp Music Club, Spencer performed “classical music, spirituals, and Creole of color songs,” 64 Parishes reported, while raising “funds for the NAACP, the Anti-Lynching Fund, and the [National Association of Negro Musicians] scholarships.”

Spencer studied music at Xavier University in New Orleans in the late 1940s, shortly before landing the job at Cohen.

Around the same time, Spencer taught music at McDonogh No. 6, an elementary school in the 13th Ward. Muhammad recalled that his work with different age groups at multiple schools made him “the music teacher for…everyone in the neighborhood.”

Even young musicians who didn’t take his classes knew Spencer as the entertainment director at Lincoln Beach, the segregated lakefront recreation complex where he booked live entertainment (Wilson “Willie Tee” Turbinton, for one, remembered Spencer taking him to gigs there).

Spencer also trained a number of musicians who became teachers themselves. Lloyd Harris, Jr., became a revered band director in his own right. Raymond Jones (better known as the artist and arranger Ray J), keyboardist/organist Sam Henry, and Maynard Chatters were as well known in classrooms as on bandstands.

In addition to his work in the schools, for years Spencer oversaw the music and served on the board of Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, then located a couple of blocks from Cohen in the 12th Ward.

When he died in 1990, Xavier held a music scholarship fund in his name.

Cohen in the hip hop era

While Professor Spencer’s work alone would secure Cohen in the annals of New Orleans music history, the school’s contributions to hip hop merit another chapter.

Jerome Temple attended Cohen in the early 1980s, and came back as a teacher in the early 90s. In the summer of 1992, he was also DJing a dance every week in the school gym as DJ Jubilee. “I used to put rappers on at one time and let them rap,” he told ANTIGRAVITY. One night his friend Tyronne Jones started dancing, and:

[He] had me laughing the way he was sliding left and right, left and right; so when I came home I just said ‘Do the Jubilee.’ So we started doing the Jubilee and the whole gym just started doing it…. Then next week, the Magnolia came with a dance: the Eddie Bauer. The Calliope came with the Jerk Baby Jerk…everybody came with a dance.

Earl Mackie and Henry Holden witnessed the phenomenon and tapped Jubilee to anchor their new hip hop label, Take Fo’ Records. After a whole summer in the Cohen gym, Jubilee said, “I had over fifty something dances on the first album.” It was a sensation, moving crowds everywhere from football stadiums to bar mitzvahs. Even as he was crowned “The King of Bounce,” Jubilee continued to teach at his alma mater.

Though bounce was dominant at the time, another Cohen alumnus, Michael Tyler, was working on more lyrical rap songs. In the late 80s, he’d played trombone in the Green Hornets marching band. A cheerleader and natural showman, he also jumped on the mic at school assemblies: “Black History Month, I had a Black History rap. Christmas, I had a Christmas rap. Whatever was going on, I had something for it,” he told OffBeat.

In 1994, as Mystikal, a one-song performance at the Treme Center impressed Big Boy Records producer Leroy “Precise” Edwards, who recorded his self-titled debut album. It caught fire, and subsequent moves to Jive and No Limit Records yielded a run of platinum albums in the late 90s and early 2000s.

Not long after Big Boy released Mystikal, the label signed the rapper Fiend fresh out of Cohen graduation. Richard Jones, Jr., who’d been rapping on stage since he was 13, also rose from Big Boy to No Limit to national success.

Big Freedia—then Freddie Ross—started at Cohen in 1992. “Cohen High sprawled the entire length of a city block. A few windows needed repair and the hallways needed a fresh coat of paint, but I was bewitched from the second I set foot on campus,” she wrote. She joined the cheerleading squad, following Mystikal’s footsteps: “cheering—with its moves and rhythm—would serve as a training ground for what would become my shows.”

In 1996 Freedia met Katey Red, who would soon enroll at Cohen as Kenyon Carter, and “we became inseparable,” Freedia wrote. Two years later, when Katey Red was a Hornets cheerleader and baton twirler, she was cajoled to rap at a block party at the Melpomene public housing development. DJ Jubilee saw the crowd go wild, and brought her to Take Fo’ Records, which released her debut album, “Melpomene Block Party” in 1999. “Just like that,” Freedia wrote, “gay rap was all the rage.”

Freedia started performing as a backup dancer and singer for Katey Red before emerging as a solo artist in the early 2000s. After Hurricane Katrina, Freedia broke nationally, and her high profile—including a long-running reality TV show—made her an important figure in the movement for LGBTQ+ rights.

The school building

Cohen opened in 1949 despite protests and a lawsuit filed by white neighbors who objected to its conversion from a white-only elementary school. Author Walter C. Stern noted that the booming Black population of Central City in the 1940s and pressure from Black activists made the change unavoidable, even for the recalcitrant Orleans Parish School Board.

The Cohen building was demolished as part of a citywide upgrade of schools after Hurricane Katrina. A new building opened on the site in 2022, when the gentrification of the surrounding neighborhood contributed to the downsizing of the student body.

Videos

A mini-documentary on Walter L. Cohen High School featuring Richard Harrison, an early student of Solomon Spencer.

Video posted by Rfemilien.

A mini-documentary on Walter L. Cohen High School featuring Richard Harrison, an early student of Solomon Spencer.

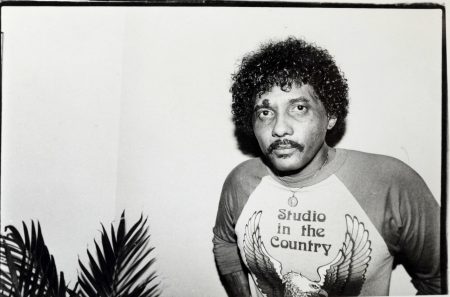

Former Cohen student Huey "Piano" Smith and the Clowns with a staged rendition of their classic "Don't You Just Know It."

Video posted by jthyme.

Former Cohen student Huey "Piano" Smith and the Clowns with a staged rendition of their classic "Don't You Just Know It."

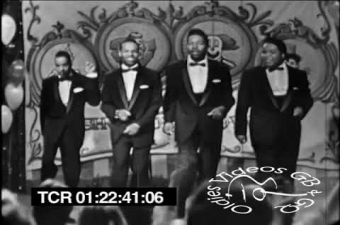

Multiple members of the Neville Brothers band, and many more musicians in their orbit, attended Cohen High School. Here they are in concert from 1991.

Video posted by Neville Brothers On MV.

Multiple members of the Neville Brothers band, and many more musicians in their orbit, attended Cohen High School. Here they are in concert from 1991.

The video for DJ Jubilee's 1993 hit, "Jubilee All," which originated in the Cohen High School gym.

Video posted by Albatross Records.

The video for DJ Jubilee's 1993 hit, "Jubilee All," which originated in the Cohen High School gym.

Images