One Stop Record Shop

350 S. Rampart StreetNew Orleans LA 70112

Legendary guitarist Earl King (“Lonely, Lonely Nights” and “Let the Good Times Roll”) claimed that he walked into the One Stop Record Shop one day in late 1963 and was told “All your gang is in the back.” Sure enough, behind the stacks of 45s and LPs he found Professor Longhair, Tommy Ridgley, Eddie Bo, and others huddled around the store’s piano.

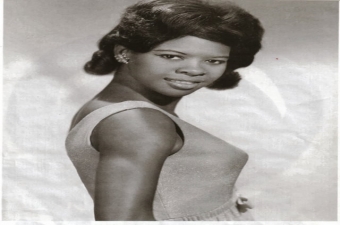

This was the same room where in early 1960 a teenaged Irma Thomas auditioned for Ron and Ric Records’ Joe Ruffino, which led to her cutting the hit “Don’t Mess With My Man” (the preceding lyric is “You can have my husband, but please…”). The record jumpstarted the career of the future Soul Queen of New Orleans.

By 1963, even before the Beatles arrived in America, things were slowing down for rhythm and blues artists in New Orleans. Professor Longhair was working at the One Stop, sweeping the floors. The place was run by Ruffino’s brother-in-law, Joe Assunto, a heavy-set, unassuming Italian American who was happy to give local musicians shelter from the storm of the British Invasion.

The store was a big inspiration for Earl King. In the mid 1960s he wrote scores of songs in its vicinity, including “Teasin’ You” for Willie Tee, “A Part of Me” for Johnny Adams, and “Big Chief” for Longhair. “Big Chief,” with its magical multi-keyboard sound, became a Mardi Gras classic, heard countless times every carnival season (though King, not Longhair, is the one singing and whistling on it).

King also wrote for Tommy Ridgley, Benny Spellman, Raymond Lewis, and others. The songs were mostly recorded for Watch Records at Cosimo Matassa’s studio on Governor Nicholls. Like Al Young down the block at the Bop Shop, Assunto was more than just a retailer. He formed the Watch label with Henry Hildebrand, owner of All South Distributors, which continued for decades under Henry’s son Warren.

Nearly all of the Watch Records sides were produced by the “Creole Beethoven” Wardell Quezerque, who finely mixed R&B, soul, and light funk. He was the arranger and co-writer of another classic conceived at the One Stop, drummer Smokey Johnson’s “It Ain’t My Fault,” which became a New Orleans parade standard.

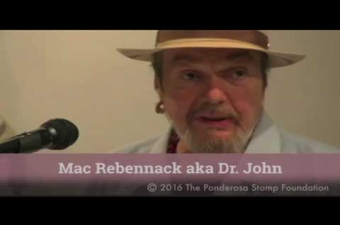

The One Stop moved from South Rampart to North Broad in 1976, and closed a year and a half after Assunto’s death in 1981. Dr. John, who hung out at the original One Stop when he was still known as Mac Rebennack, recalled, “Joe Assunto was a really beautiful person.”

About South Rampart Street

South Rampart Street was the main commercial corridor in “back o’ town,” originally a swampy area at the back end of the city where New Orleans’ racial order relegated black residents in the late 1800s. The strip filled with businesses—many run by Jewish, Italian, and Chinese merchants—catering to a black clientele. Among these were dance halls, juke joints, tailors who outfitted bands with uniforms, and pawn shops that bought and sold instruments.

Churches here tended to be Protestant, with emotive spirituals and hymns in their services that reverberated through the neighborhood. To the ministers’ chagrin this area included Black Storyville, the red light district for those barred from the whites-only bordellos and gambling houses just across Canal Street. This traffic fueled some social ills. It also helped attract audiences for working musicians. (Business continued after 1917, when the white vice district—Storyville—shut down).

In 1938, the WPA City Guide called South Rampart “The Harlem of New Orleans.” It was full of music, from barrelhouse piano players like Tuts Washington to big bands like Papa Celestin’s. The street itself was a venue, with benevolent societies and social clubs parading with brass bands, and, on Carnival, the Zulu parade, Baby Dolls, and chanting bands of Mardi Gras Indians.

The strip was referenced in popular songs, from the traditional jazz tune “South Rampart Street Parade” to Louis Jordan’s jump blues hit “Saturday Night Fish Fry” in 1949, about a house on Rampart “rockin’” till the break of dawn.

While the “New Orleans sound” of R&B played across the country in the 1950s, South Rampart Street went the way of other black inner city neighborhoods in the age of urban renewal. Whole blocks were demolished and redeveloped, paving the way for a new city hall and today’s Central Business District.

Videos

From the 2009 Ponderosa Stomp Conference panel "Wardell Quezergue, Mac Rebennack, Bob French," Rebennack talks about recording with Quezergue and Professor Longhair.

Video © The Ponderosa Stomp Foundation. Cannot be used by third party without written permission.

From the 2009 Ponderosa Stomp Conference panel "Wardell Quezergue, Mac Rebennack, Bob French," Rebennack talks about recording with Quezergue and Professor Longhair.

From the 2017 Ponderosa Stomp Music History Conference, Richard Campanella, Bruce Raeburn, and "Deacon" John Moore discuss music on South Rampart Street with Jordan Hirsch.

Video from Ponderosa Stomp.

From the 2017 Ponderosa Stomp Music History Conference, Richard Campanella, Bruce Raeburn, and "Deacon" John Moore discuss music on South Rampart Street with Jordan Hirsch.

From WWOZ's Tricentennial Moments: Irma Thomas.

Images