Carnival Time: Mardi Gras Parade Route Tour

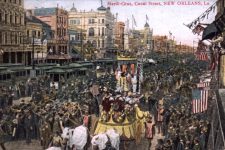

This tour features sites within a few blocks of New Orleans’ main Uptown Mardi Gras parade route, from the vicinity of Napoleon Avenue to Canal Street.

Near Napoleon Avenue

The 13th Ward, a wedge of Uptown between Jefferson and Napoleon Avenue, has a particularly rich musical history, especially where Carnival is concerned.

F&M Patio featured many of the city’s R&B greats, including “Deacon” John Moore, who played guitar on “Big Chief” by Professor Longhair. Le Bon Temps Roule, formerly home to jazz pioneer Leon Ropplo, hosts Black Masking Indians from the neighborhood.

Benny’s Bar was once frequented by Big Chief Jolly, the leader of the Wild Tchoupitoulas and role model to his nephews, the Neville brothers, who grew up a few doors down. The Neville family home doubled as a practice facility for the Hawketts, led by Art Nevillle, who recorded “Mardi Gras Mambo” in 1954.

One of the Hawketts’ drummers, now known as Idris Muhammad, lived around the corner, and played the first gig of his world-spanning career on the back of a truck on Mardi Gras Day in the 1940s. The Hawketts also performed at Valencia Hall, as did Sugar Boy Crawford of “Jock-A-Mo” fame.

On the 12th Ward side of Napoleon, Tipitina’s has been integral to Carnival celebrations since opening in 1977, and was named in honor of Professor Longhair, whose music has been a staple of the season for generations. The Walter L. Cohen High School marching band gained citywide acclaim for its appearances in Mardi Gras parades, and produced leaders of traditional jazz and brass bands including Gregg Stafford and Herbert McCarver.

Central City

On Louisiana Avenue, the Nite Cap was foundational for The Meters, who have provided much of Carnival’s soundtrack since the 1970s. The Golden Comanche Black Masking Indians came out of the Sandpiper Lounge on Mardi Gras Morning for years. Dr. John, another major contributor to the Mardi Gras canon, was among the musicians who frequented jazz shows at Vernon’s.

A depiction of Dr. John in full Night Tripper regalia covers a two-story wall nearby. The club once known as Newton’s was vital to the emergence of bounce music, which can be heard as frequently on the parade route as the R&B classics.

Joe Oliver’s house is below Washington Avenue. Oliver, Louis Armstrong’s mentor, came up in brass bands that marched in Uptown parades. The Glass House was a home base for the Rebirth Brass Band, who crossed over to mainstream audience with the Mardi Gras hit “Do Watcha Wanna.”

The H&R Bar held practices of the renowned Wild Magnolias, pioneers of recorded Mardi Gras Indian music. Across Jackson Avenue, Victor Augustine’s Curio Shop was a portal to the record business for Earl King, who provided the vocals and whistling on “Big Chief” after Professor Longhair left the studio early.

Central Business District

That “Big Chief” session was produced by Wardell Quezergue, who taught at the Grunewald School of Music. Quezergue also arranged horn parts for Meters records cut on the next block of Camp Street, at Cosimo Matassa’s Jazz City Studio.

The legendary Jelly Roll Morton, who said he was a Spy Boy in a Mardi Gras Indian tribe around the turn of the 20th century, hung out at the Red Onion. This is the first of ten sites on South Rampart Street, once the commercial backbone of a predominantly Black neighborhood.

Mr. Google Eyes sang at the Downbeat Club decades before he became a fixture on Bourbon Street, a locus of Mardi Gras mayhem. The Little Gem Saloon was on a parade route; in the 1930s, a WPA photographer found Baby Dolls dancing out of its door.

When Louis Armstrong reigned as King Zulu in 1949, he stopped at the Karnofsky shop and residence to say hello to the family that employed and supported him in his youth. Iroquois Theater regular Clarence Williams composed “Brown Skin (Who, For You),” a hit that took over Mardi Gras parades in 1916.

The Eagle Saloon, namesake of the Eagle Band and the Eagle Brass Band. The latter employed some of the city’s finest brass band musicians, who were regular performers during Carnival.

The One Stop Record Shop was a base of operations for Earl King when he wrote “Big Chief.” The Bop Shop facilitated an early recording by bandleader Dave Bartholomew, an architect of New Orleans R&B including Carnival standards such as “Mardi Gras in New Orleans.”

The Astoria Hotel featured Papa Celestin, a veteran of brass bands that marched in Mardi Gras parades. In the 1940s, Morris Music played the latest records through speakers on the sidewalk, likely including the earliest Carnival records of the R&B era.

The Hackenjos Music Company, an early 20th century publisher of ragtime sheet music, overlooked the Canal Street parade route. Danny Barker, who made what is probably the first recording of the Mardi Gras Indian touchstone “Indian Red,” performed at the Alamo Dance Hall.

Werlein’s Music Store provided instruments, equipment, and sheet music to generations of New Orleans musicians. Fats Domino, who recorded “Mardi Gras in New Orleans,” bought his Steinway pianos here.

Places in this Tour

- F&M Patio

- Le Bon Temps Roule/Roppolo residence

- Benny's Bar

- Neville Family Home

- Idris Muhammad's apartment

- Valencia Hall

- Tipitina's

- Walter L. Cohen High School

- The Nite Cap

- Hayes' Chicken Shack/Vernon's

- Sandpiper Lounge

- Dr. John Mural

- Newton's/Guitar Joe's House of Blues/Portside Lounge

- Joe “King” Oliver’s House

- The Glass House

- H&R Bar

- Victor Augustine's Curio Shop

- Grunewald School of Music

- Jazz City Studio

- Red Onion

- Downbeat Club

- Little Gem Saloon and Buddy Bolden Mural

- Karnofsky Shop and Residence

- Iroquois Theater

- Eagle Saloon / Odd Fellows and Masonic Hall

- One Stop Record Shop

- The Bop Shop

- Astoria Hotel

- Morris Music

- Hackenjos Music Company

- Junius Hart Piano House and Alamo Dance Hall

- Werlein's Music Store