New Orleans/Mahalia Jackson Theater for the Performing Arts

1419 Basin StreetNew Orleans LA 70116

To visit this site, enter Louis Armstrong Park at 801 N Rampart Street and proceed past the sculptures and the Municipal Auditorium, to the far side of the lagoon.

The States-Item reported an “air of glamour” on opening night of the New Orleans Theater for the Performing Arts in 1973, noting the building’s plush red interior and a “$49,000 chandelier composed of delicately balanced prisms” in the lobby. A long-awaited home for opera and classical music in the city, the venue featured state-of-the-art equipment, a pit for 90 musicians, and acoustics designed by the renowned Dr. C. P. Boner.

Its inaugural concert was a performance of Verdi’s Requiem by the New Orleans Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra, with a solo by native born bass-baritone Norman Treigle. On an upper level of the lobby after the performance, the conductor, Werner Torkanowsky, “positioned himself on a banister and slid to the next lobby level in an uncharacteristic display of enthusiasm.” A violinist and composer as well as a conductor, Torkanowsky led major orchestras across the country and overseas, spending 14 years at the helm of the New Orleans Philharmonic. (His son, David Torkanowsky, would become a first-call pianist on the local scene and a DJ on radio station WWOZ.)

At the premier, former mayor Victor Schiro, whose administration had earmarked millions for the venue, said he felt like he was being presented “with a very beautiful and wonderful son.” As mayor in the 1960s he’d supported bulldozing four adjacent residential blocks of Treme, hoping to build a larger “cultural center” on the land. Those plans fell through in the 70s, and the theater became a stand-alone, all-purpose venue, hosting an array of stage productions and serving as home base for the New Orleans Philharmonic and the New Orleans Opera House Association.

Local opera lovers hoped the new digs would help the city regain some cachet. There was a time in the 19thcentury when New York had looked to New Orleans as the leading presenter of opera in America, a status embodied in the city’s French Opera House. Opening in 1859, the Opera House was a point of pride for the Creole elite, a monument to their Old World sophistication. When it burned down in 1919 the Times-Picayune feared for the city’s cultural decline (for the newspaper, “culture” was exclusively of European origin; in 1918 it denounced jazz as an “atrocity” in racist and classist terms). The next long-term home for opera in New Orleans, the Municipal Auditorium, was associated with American industry, serving as a convention center as well as a concert hall when it opened in 1930. Presenting opera in a glitzy, dedicated cultural hub was regarded by some as a return to form.

In addition to opera, New Orleans has a proud tradition of classical music, and the city’s Symphony Orchestra attracted Maxim Shostakovich, son of legendary composer Dmitri Shostakovich, to be its music director in 1986. Amid budget issues in 1990, though, the orchestra’s board failed to pay him, and the following year, with severe cuts to programming in store, he resigned. Some 65 of the orchestra’s musicians, appalled by their management, banded together to form the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra in 1991, taking on governance and administrative roles themselves. The LPO, now the oldest musician-run orchestra in the United States, spent years based at this theater.

The city renamed the venue for New Orleans’ own gospel music icon Mahalia Jackson in 1993, an active period for organizers making public claims of the city’s African American cultural heritage (advocates secured nearby Congo Square’s addition to the National Register of Historic Places that same year). In 2005, when the levees failed during Hurricane Katrina, 14 feet of water flooded the theater’s basement, destroying its electrical and mechanical systems. Renovation was relatively swift, and it reopened in 2009 with upgraded sound and lighting.

For more about Louis Armstrong Park, click here.

Videos

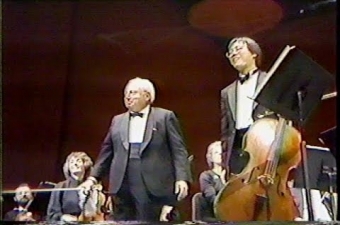

Werner Torkanowsky, Music Director of the New Orleans Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra for much of the 1960s and 70s, conducts Yo Yo Ma in 1986.

Video posted by Steven Honigberg.

Werner Torkanowsky, Music Director of the New Orleans Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra for much of the 1960s and 70s, conducts Yo Yo Ma in 1986.

Maxim Shostakovich in 1985, shortly before he became the last Music Director of New Orleans Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra.

Video posted by PianistlavFastlovsky.

Maxim Shostakovich in 1985, shortly before he became the last Music Director of New Orleans Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra.

Images