Benny’s Bar

938 Valence StreetNew Orleans LA 70115

Benny’s, a tiny corner barroom deeply rooted in the 13th Ward, became an unlikely hot spot for late-night blues and roots music between 1984 and 1997.

When the bar started hosting shows in the wee hours with no cover charge, neighborhood regulars were joined by a mix of hardcore music fans, college students, musicians looking to jam after other gigs, and assorted figures of the night. As guitarist Mark Boudousquie told the Times-Picayune in 1988, summing up Benny’s appeal, “It’s an anything-goes kind of place.”

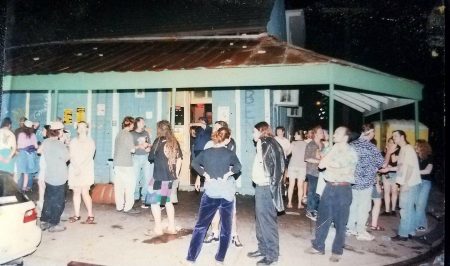

The bar was in an old Creole cottage—often described as “ramshackle” and “the size of a living room”—with a rusty wrap-around awning. Pianist Jon Cleary, who accompanied blues singer Mighty Sam McClain here in the mid-80s, posted this remembrance:

It had a small bar to the left of the corner door and the wall to what had once been the adjoining room had been torn down by someone with a hammer leaving bare two-by-four support beams holding up the ceiling, with old nails still sticking out. This cramped space functioned as the stage area with a bit of carpet on the slab floor. It had speakers from a PA system that looked like it had been there since world war one and, prominently placed in front of the ’stage’ on a rickety wooden chair, sat the ‘Kentwood jar’, a giant plastic bottle for tips. Mood lighting was achieved by unscrewing one of the bare naked light bulbs hanging from the ceiling. The few extra dollars divvied out at the end of the night, usually around four in the morning, would bring my pay up to a princely forty dollars for a four hour show.

About that slim-necked Kentwood jug, author Jay Mazza noted: “Money went in fairly easily, but it was difficult to get the bills out…Eventually someone cut a special trap door in the side of the bottle to facilitate removing the cash.”

The loose, down-home vibe came with some cachet courtesy of the Neville brothers, who lived on the next two blocks of Valence Street while building a national profile in the 80s—it was Cyril Neville who instigated the bar’s development as a music venue.

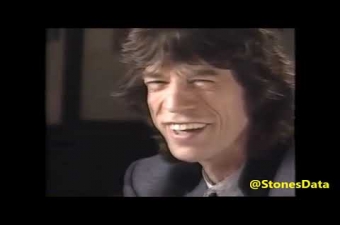

As Mazza writes, Benny’s “grew into the hippest late-night music club in the city, drawing Hollywood stars…and musicians known the world over.” Members of the Rolling Stones or ZZ Top might sit in for a set; John Goodman or Lisa Bonet might be at the bar. Harmonica player J.D. Hill, a regular performer, saw Benny’s drawing power for celebrities like this: “You just go to Benny’s—ain’t nobody going to bother you. They don’t give a damn who you are.”

From Callaghan’s to Benny’s

For most of the 20th century, the place had been just a neighborhood corner store and bar—the Neville brothers went there as youngsters, when it was known as Jack Callaghan’s. In the excellent group memoir The Brothers Neville, Cyril recalled the excitement of going there with his uncle George Landry, later known as Big Chief Jolly of the Wild Tchoupitoulas Mardi Gras Indians:

There was a section for white people up front and a side door for blacks, who had to sit in the back room. The back room was the happening room. I can still smell the beer and hear the tinkle of glasses, the raucous laughter and Ray Charles shouting “I Got a Woman” on the jukebox.

Around 1978, a Black man named Benny Jones (not to be confused with the brass band drummer of the same name) took over the business, and his relationship with the Nevilles deepened the family’s connection to the place. Author Bryan Wagner writes that “The Wild Tchoupitoulas practiced here on occasion and early versions of the Neville Brothers played shows here in the late 1970s.”

Cyril Neville’s drive “to preserve identity”

Cyril Neville started playing regularly at Benny’s specifically to preserve New Orleans’ neighborhood-based culture.

Big Chief Jolly and Professor Longhair passed away in 1980, and James Booker, a lifelong friend of the Nevilles, died in 1983. None lived past age 65. The losses left Cyril feeling that the Black men who “molded our musical universe” were disappearing.

The spring of 1984 brought both the opening of the World’s Fair in New Orleans, which presented local music in a tourist-oriented spectacle, and the closing of Tipitina’s, an artist-centric venue a few blocks from the Nevilles’ homes that was vital to their success (Tipitina’s would reopen in 1986, but no one knew that at the time).

Cyril told Wavelength that “The neighborhood bar and the local star are becoming an endangered species.” In the summer of 1984, he formed a trio called Endangered Species with Charles Moore and Terry Manuel, each of them the youngest brother of a musical family in the 13th Ward, and starting jamming at Benny’s.

“The main thing was to have something in our own neighborhood,” he explained to the Times-Picayune. “A place to grow musically, culturally, spiritually. It gave us a chance to capture and preserve our culture. Benny’s is our laboratory, where we go to fine tune our stuff, to create little monsters.”

Endangered Species didn’t last long, but around 1985 Cyril assumed leadership of the Uptown Allstars, a band his nephew Ivan Neville had helped put together. Its lineup varied, but often included rhythm players in the Neville Brothers band, like drummer “Mean” Willie Green.

Mazza writes that the Uptown Allstars were playing weekly at Benny’s by 1986, and “quickly became an institution.” With Neville’s group as an anchor, the bar introduced a full slate of live music.

From corner bar to “cultural phenomenon”

A 1988 listing for Benny’s in the Times-Picayune advised, “Most of the time the week’s lineup is decided at the last minute, so if you want to know who’s playing before you go give them a call.”

Bookings leaned toward the blues. J.D. and the Jammers, led by harmonica player J.D. Hill, was a mainstay, and fixtures of the city’s Black clubs like Walter “Wolfman” Washington and Johnny Adams cycled through.

The bar also presented a healthy roster of artists living in the neighborhood, including “Deacon” John Moore and J. Monque’D. The latter also plugged Benny’s on his blues show on community radio station WWOZ, which expanded its audience.

By the late 80s Cyril Neville’s vision was realized—a hole-in-the-wall on his corner had become a “cultural phenomenon,” the place to go for live music when every other show was over.

A band called New Orleans Blues Department held down Thursday nights in this period, with a young Bruce “Sunpie” Barnes on harmonica, and Stephen Holt, better known as Red Priest, on guitar.

Priest also played here with the Songdogs, a roots-rock group fronted by Allison Young and Lisa Mednick. They were two of several women to regularly lead bands at Benny’s, along with Charmaine Neville (daughter of Charles Neville), Irene Sage of Irene and the Mikes, and Paula Rangell of Paula and Pontiacs.

The mainstream finds Benny’s in the 1990s

The bar was written up in the New York Times in 1990, and more mainstream institutions took an interest in the business in the ensuing years, which may have ultimately shortened its life.

Benny’s got on the radar of BMI, the composers’ rights organization that collects annual fees from nightclubs to license performances of registered songs. The bar had never paid for a license, so BMI sued. In 1992 the City of New Orleans announced that it would pursue a lawsuit against the club, too, for violating a zoning ordinance forbidding stage acts.

Most damaging, though, was attention from New Orleans Police Department. Two nights before Thanksgiving in 1992, NOPD used the bar as a test case for a new tactic “to combat narcotics trafficking.”

Police said that Benny Jones’ brother Lenny, who helped run the place, sold two quarter-gram bags of cocaine to an undercover cop, and used the proceeds for the bar. According to the Times-Picayune, NOPD claimed that this enabled them to seize “all bank accounts, and assets including liquor and a pool table” from the business.

On top of that, Benny was arrested for failing to enforce a state regulation meant for strip clubs, which prohibited dancing within three feet of a performer. Benny was released without being charged, and had the bar back in action by New Year’s Day in 1993.

However, the Jones brothers closed the bar after Jazz Fest that spring. A document apparently from the Jones family suggests that the property owner forced them out. The bar was dark for six months before prosecutors dropped the charge against Lenny. The NOPD’s tactic failed in court, but succeeded in derailing Benny’s.

Second and third lives as Pasquallie’s and Blue Jackal Bar

In early 1994, the owner of the building, who’d operated the barroom before Benny Jones, reopened it as Pasquallie’s, with “a little fresh paint” and “two security lights to cut down on the drug trafficking.”

The music picked up more or less where it left off, with the notable addition of a funk band called Galacitc Prophylactic. As one might deduce from the name, it was composed of college students (who, before too long, adopted the more dignified moniker Galactic). Its members had been regulars at Benny’s—when it got shut down, a few of them kept one of its doors as a trophy in their living room.

According to Mazza, Galactic met vocalist Theryl “Houseman” DeClouet at the bar. Tapping the veteran soul singer as a front man provided the youngsters with a mentor and with credibility outside of the college scene. Health issues sidelined DeClouet in the early aughts, but Galactic evolved into one of New Orleans’ more successful touring acts.

Pasquallie’s continued to book artists with ties to the neighborhood, including next-generation Nevilles Ivan and Charmaine, and the bassist and bandleader Walter Payton, who grew up a few blocks away. Celebrities continued dropping by, including the Rolling Stones, who’d toured with the Neville Brothers in the 80s (they’d also toured the Meters, with Cyril on percussion, in 1975). Nevertheless, this incarnation of the club lasted less than a year and a half.

A third version opened in August 1995 under the name Blue Jackal Bar, with a revamped stage and spruced up interior. In addition to blues by the likes of Ironing Board Sam and Marva Wright, the Blue Jackal presented some classic R&B artists, including Ernie K-Doe in the early stages of his comeback, and sprinkled in progressive acts like Coolbone and All That, which fused brass instruments with hip hop. The place folded in six months.

The failure of Benny’s without Benny

Despite the general continuity in format—late-night, no-cover roots music, with jamming encouraged—the social dynamic around the bar shifted after Benny Jones’ departure.

Jones grew up in the 13th Ward and had longstanding relationships with the folks living nearby; before the bar became a scene, its regulars were older, working-class Black residents of the area, like Big Chief Jolly.

These relationships were foundational to the bar’s success. When Jones went all-in on live music in 1986, Aaron Neville, on the next block, could “hear the bass and the drums coming up through the floor of my bedroom at three in the morning.” Still, Jones said, “I don’t really get complaints” from neighbors.

The Blue Jackal, however, looked more to students and visitors to the 13th Ward to bring in money. In theory, this was in keeping with Cyril Neville’s original vision. As he explained to Wavelength in 1986:

What we’re mainly about is the struggle to preserve our musical heritage by having it known to as many people as we can…I think everybody should be aware of how great the gift is that Africa gave America. Not only Blacks, but everybody should get a little more hip to it.

In practice, however, as the crack epidemic ravaged the neighborhood in the early and mid-90s, the Times-Picayune reported that “At least one previous tenant of 938 Valence said attendance was hampered by the perception of some music fans that the neighborhood around the club is unsafe.”

When yet another operator took over the place in 1996, remodeled, and opened under the name Benny’s Blues Bar, Art Neville, still living on the 1100 block of Valence, said “Put police around there, and it will work.”

Once again, bookings followed familiar contours, with shows by the likes of headstand enthusiast “Ready Teddy” McQuiston, and musicians from the neighborhood such as the Caesar family. But the latest proprietors couldn’t replicate the Jones brothers’ success either.

Without a personal connection to its management, and with crime surging, neighbors regularly called the cops about Benny’s. After a 1997 hearing featuring “testimony about instances of public sex, public urination, loud noise, drug-dealing, gunfire, trash-dumping and not having a manager on the premises,” City regulators shut down the bar for good.

The rise and fall and rise of the cottage at 938 Valence

The fate of Benny’s iconic building tracked the larger social and economic trends in the 13th Ward.

The original Creole cottage that housed the bar was built in 1870, and became a corner store and saloon in 1890. The first Callaghan, an Irish immigrant, bought it in 1899, and tacked on a two-story addition for his family to live in.

The business stayed in the family for generations, and the building stayed even longer—Aaron Neville told A Closer Walk that Benny Jones used to work for Callaghan descendants, and asked them to lease him the place in the 1970s, as white flight was changing the area’s demographics.

The family retained ownership of the building until 1996, when the neighborhood’s economic prospects looked bleak, and the owner, who’d retired to the North Shore of Lake Pontchartrain, told the Times-Picayune that he didn’t “have the time or inclination anymore to fool with it.”

However, while the crack epidemic hit the neighborhood late, with effects persisting well into the 1990s, gentrification came early, before Hurricane Katrina in the 2000s (the area’s proximity to affluent parts of Uptown and its historic architecture made it attractive to investors).

In 2000, after a tropical storm had claimed the building’s distinctive awning, a preservationist bought the property to renovate it as a residence. While work was underway, the cottage collapsed. To save it, the Callaghan’s century-old two-story addition had to be removed. The original barroom was set on a new foundation and joined to a new, single-story extension.

The reconstructed house became a registered historic landmark. Though it could no longer be confused for Benny’s Bar, the bare studs that framed the Neville family’s first performances there still stand inside its walls. The bar “as big as a living room” is now a living room.

Today, with New Orleans’ neighborhood bars and late-night music more endangered than ever, few lost venues inspire as much devotion as Benny’s. As Jon Cleary wrote, “Grimy, greasy, grungy and grumpily great…it seemed a metaphor for the city I love. I really miss that place and those times.”

Videos

A look inside the club best known as Benny's in 1994, when it was called Pasquallie's, and the Rolling Stones dropped by.

Video posted by RollingStonesData.

A look inside the club best known as Benny's in 1994, when it was called Pasquallie's, and the Rolling Stones dropped by.

The opening sequence of this televised Neville Brothers concert from 1989 includes a quick shot of the exterior of Benny's Bar.

Video posted by Pickanik.

The opening sequence of this televised Neville Brothers concert from 1989 includes a quick shot of the exterior of Benny's Bar.

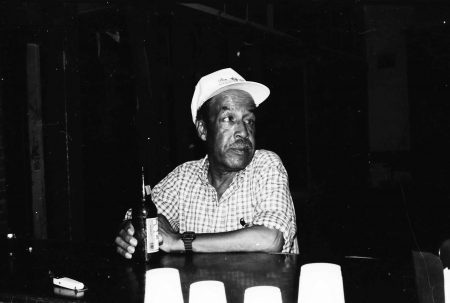

Images