Dixie Taverne

3340 Canal StreetNew Orleans LA 70119

The Dixie Taverne was a hub for New Orleans’ underground music scene, with an emphasis on punk and metal, from the mid-1990s until 2005, when the levee breaches caused by Hurricane Katrina swamped it under six feet of water. The building had housed other nightclubs going back to 1952, many of which featured artists from Latin America.

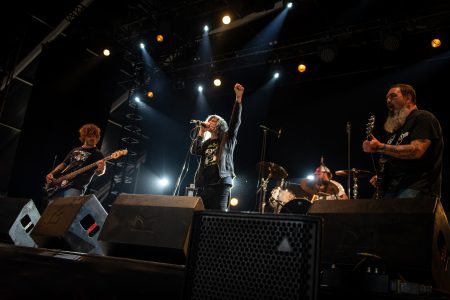

Dixie’s run of “Extreme Music,” as it was advertised in the zine Paranoize, began after Maurice and Maribel Piza bought the place in 1994. The Pizas started off presenting roots music like Coco Robicheaux, but, according to Michael Patrick Welch, changed formats after a bartender asked to book a friend’s band, sludge metal heroes Eyehategod.

Eyehategod’s association with Dixie continued when its bassist, Gary Mader, and his wife, moved into the apartment above the venue, which he called “NOLA’s CBGB” (its men’s room was as harrowing as the one in the fabled New York City club). The band recorded upstairs, and Mader jammed there with his other bands, Outlaw Order and Hawg Jaw. He booked shows downstairs, too.

Other heavy artists gravitated to the club, including vocalist Troy “T.Roy” Medlin, who also booked shows here. Dax Riggs, whose metal band Acid Bath garnered a cult following in the 90s, played at Dixie with a later project, Deadboy & the Elephantmen, which signed to Fat Possum Records (the label described that band as “country punk garage folk”).

“King Louie” Bankston (1972 – 2022), an influential songwriter and artist, was another regular performer at here. He performed as a one-man band with a kick drum, guitar, and harmonica; behind a full drum kit with the Royal Pendletons, garage rockers produced by the legendary Alex Chilton; and on guitar and vocals with other collaborators.

Experimentation across groups and genres

Collaboration across multiple bands was constant in this scene: Andy Goceljak and Marvin Hirsch, for example, played in hardcore punk band The Pallbearers at Dixie, while joining drummer Paul Artigues in Die Rotzz, which became another fixture at the club (Artigues and Hirsch also teamed up to back Ninth Ward bluesman Guitar Lightnin’ Lee).

Dixie attracted touring acts, too, from as far as Portugal and Japan. For musicians and fans of a certain bent, the club was an oasis, a place where anything could go. While metalheads and punks found their tribes here, its low-slung stage—facing a vertical metal beam that was met occasionally by a forehead—welcomed other acts that defied categorization.

Egg Yolk Jubilee, which serves a singular mélange of jazz and rock, got its start at Dixie in 1996, as the Panéed Syncopators. Trumpeter/singer Eric Belleto told William Archambeault of ANTIGRAVITY, “Everyone in the club was wearing black leather and spikes. We were wearing plaid shorts and t-shirts.” The band tried to annoy the crowd, Belleto recalled, “but they liked us” (they shared the instinct to antagonize with Eyehategod, whose signature slowed-down tempos began as an affront to prevailing tastes in metal in the late 1980s).

At a time when New Orleans rappers were topping the Billboard charts, Dixie also hosted some underground hip-hop shows. The club remained best-known, though, for heavy music shouted and shredded at brain-squishing volume; in the summers before Hurricane Katrina, it hosted the aptly named Earbleed Fest.

After its demise in the flood, the club was memorialized in the song “Taking Back Dixie Taverne” by Fat Stupid Ugly People, the trio fronted by Hollise Murphy, which performed there in its heyday.

Early history

After spending the first half of the 20th century as a pharmacy, this building was converted to a music venue—the Lotus Room—in 1952. One of the men behind the project, Carl Liller, was also the proprietor of the Uptown venue that became the Nite Cap, the launching pad for the Meters, whose style, especially Zigaboo Modeliste‘s drumming, would later influence the sound of the city’s metal.

Liller and his partner soon sold the Lotus Room to Bob Olsen and his wife Rose, who was a member of one of the city’s most prominent Jewish families of the first half of the 20th century, the Shushans.

The club’s piano bar featured solo acts including Bobby Quinton, born Juan Roberto Quinton, who also led a “favorite Latin combo” in town, according to Down Beat (Quinton would open a club of his own nearby on Tulane Avenue in 1965).

The Lotus Room was an after-hours destination “for theater-goers and night-clubbers who relish a light, appetizing snack to the accompaniment of entertaining music,” as the New Orleans Item wrote. Its emcee hosted a radio show from the bar that aired from 12:30 till 2:30 in the morning.

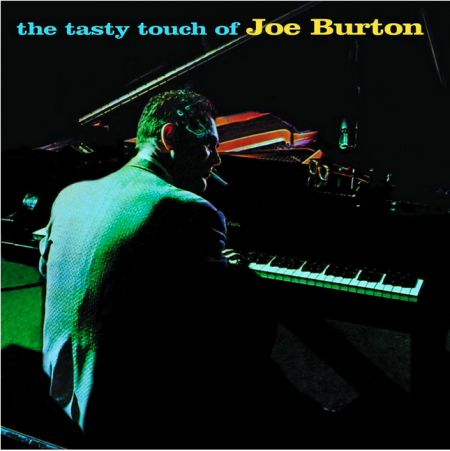

In 1958 the Olsens sold the club to Joe Burton, a jazz pianist who, according to musician and author Charles Suhor, maintained the persona of an “artiste who came down from New York, Baby, to bring hip and cool sounds to the provinces.”

Burton put his name on the club and advertised it as “New Orleans’ only modern jazz room.” (It may have been the only one dedicated exclusively to bebop at the time, but progressive Black audiences, denied entry here under Jim Crow, could find cutting edge jazz elsewhere, including Hayes’ Chicken Shack.)

Suhor accompanied Burton at his club, including for a TV spot in 1960. As Suhor recalled, “There was an offbeat charisma in Burton’s moody posing that attracted those who romanticized the modern jazz artist as a misunderstood hero.” Less enthralled were fellow modernists like reed man Al Belletto, a forebearer of Egg Yolk Jubilee’s trumpeter Eric Belletto, who recalled Burton kicking him out of the club for no reason.

A legacy of Latin music

In 1962 Burton split town and the venue once again changed formats. Across the country and in New Orleans, white audiences found their way to Latin music in the 1950s and early 60s. The same trend that fueled Chris Owens’ maraca routine in the French Quarter gave rise to the Bongo Room here.

In 1964, new proprietors dubbed it Club Mocambo, borrowing the name of a famous Hollywood nightspot. They presented artists including Ruben Gonzalez, who was born in Cuba and found success in New York as a singer and RCA recording artist before settling in New Orleans. He claimed credit for introducing salsa music to the city, becoming known locally as “Mr. Salsa.”

Club Mocambo billed itself as “New Orleans’ only authentic Latin club,” and could back up the claim: The surrounding Mid-City neighborhood had one of the highest concentrations of Hispanic residents in New Orleans. The club hired a Spanish-speaking bartender, and Mr. Salsa became a part owner.

Following Gonzalez’ run, the club’s entertainment declined—offerings in the summer of 1978 included a wet t-shirt contest and “free disco lessons.” The building eventually lost its license to present live music (at which time it hosted a comedy night with Ken Jeong, then an unknown local medical resident, who would get famous after a full monty appearance in the movie The Hangover).

After numerous name changes, the club became the Dixie Tavern in 1990 (the second -e was added to “Taverne” later). Its patrons may have associated the name more readily with locally brewed Dixie beer than with the Confederacy itself, but the club sat on a parkway named for Confederate president Jefferson Davis—a statue of whom stood right outside the bar (it came down in 2017, and the street was renamed for civic leader Norman C. Francis, who is Black, in 2020).

While the club’s clientele remained predominantly white, its most devoted patron was an African American elder called Broadway Joe, who embraced the community of rockers and underage rascals that eventually flocked to the place (when Atlanta’s Black Lips recalled playing here for an audience of one, they were likely referring to him).

The artists on stage were also mostly, but not exclusively, white. Co-owner Maribel Piza, who is Cuban American, continued the club’s legacy of Spanish-language music in the late 1990s when she booked Barrikada, a local rock band whose members hailed from Mexico, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. She added some Latin rock CDs to the jukebox, and Barrikada shows at Dixie became gatherings for a young Hispanic crowd.

Videos

"NOLA: Life, Death and Heavy Blues from the Bayou," a 76-minute documentary from Noisey about New Orleans metal produced in 2014.

Video by Fleshlips.

"NOLA: Life, Death and Heavy Blues from the Bayou," a 76-minute documentary from Noisey about New Orleans metal produced in 2014.

"King Louie" Bankston performs as a one-man band at Dixie Taverne ca. 2002.

Deadboy & The Elephantmen live at Dixie Taverne in 2001.

Fight the Goober, a spectacle of music and (very) amateur boxing at Dixie Taverne from 2002.

Video by paranoize.

Fight the Goober, a spectacle of music and (very) amateur boxing at Dixie Taverne from 2002.

A 30-minute documentary on Ruben "Mr. Salsa" Gonzalez from Ecos Latinos.

A long conversation with Maribel Piza, co-founder of Dixie Taverne.

Video by Rehearsal Space Invaders.

A long conversation with Maribel Piza, co-founder of Dixie Taverne.

Images