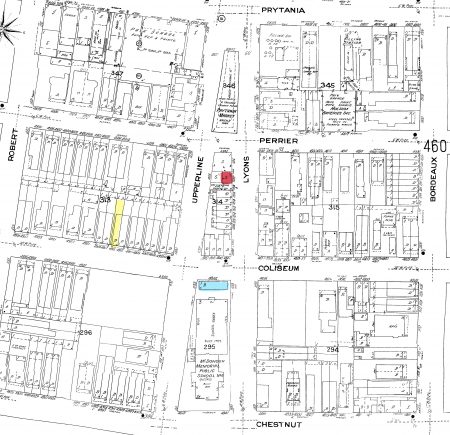

Idris Muhammad’s apartment

1220 LyonsNew Orleans LA 70115

The famously versatile and influential drummer Idris Muhammad played on platinum records, toured the world with titans of jazz, and supplied beats for countless hip hop producers–all with a rhythmic vocabulary formed in the 13th Ward of New Orleans in the 1940s and 50s.

“All my rhythms are based on two elements,” he wrote, “the Second Line bass drum patterns, and the tambourine rhythms from the Indians dancing at Mardi Gras.”

Music in the home

Muhammad was born Leo Morris in 1939. He grew up in a shotgun house on Coliseum Street with no bathroom before moving in the early 1950s to a three-room apartment with indoor plumbing in a cinder block building around the corner on Lyons Street. As he wrote:

These apartments are attached to [a] bar and [a] pool hall where the guys are playing Nine Ball and drinking beer, so we can hear their music coming in through the walls. We hear that all day and all night. Do you know how much music is in this neighborhood?

A healthy portion of that music came from the Morris residence itself. In addition to his father singing and playing the banjo, all of Muhammad’s brothers played the drums.

We always have drums set up in the living room against a window facing the street .. .A lot of guys’ families didn’t like the drums in the house … My mother would let us play so they would all come to my house to practice. Every day from noon to five we had all these drummers in my house.

As he told All About Jazz, “Earl Palmer was there. Ed Blackwell was there. John Boudreaux and Smokey Johnson”—world-class talents who moved fluidly between rump-shaking R&B and heady modern jazz.

Cyril Neville, who lived a few blocks away, remembered passing by with future Meters drummer Zigaboo Modeliste when they were kids:

We’d listen to Leo Morris, who lived next to Buddy’s Cleaners, practicing his drums. Leo had the funkiest beats. Studying his style, I’d lean my head so intensely on the screen door in front of his house that I’d have marks on my skin.

The cleaners next door (the side opposite the pool hall) provided even more sound for Muhammad to absorb: “I found myself trying to duplicate the sound of these steam pressure machines on the hi-hat cymbals,” he wrote. “This becomes part of the rhythm for our neighborhood.”

Nurturing his talent, Muhammad’s his mother gave him a tape recorder for his 13th birthday: “I listened back at that machine to develop my sound,” he would write. “That’s why I play the bottom a lot … I could hear the bass drum coming back at me … That’s why my foot is so strong.”

Music on Mardi Gras

As with many other musicians from the 13th Ward, Carnival was foundational to Muhammad’s musical life:

On Mardi Gras day there are parades from morning until night. As the parade would second line, that bass drum attracted me because it was so big and loud. The bass drum player has got a cymbal turned upward on top of the bass drum. There’s a coat hanger wrapped in a circle and stuffed down on a broom handle that’s been cut off. I would get underneath the bass drum as the band would come by and I would dance to it. I was that small! And the bass drum guy would say: “Move your ass away from here before I hit you with this mallet.”… There’s a thrill of being inside a parade.

Mardi Gras Day was the occasion for Muhammad’s first gig, when he was just eight or nine years old. A group of “old Dixieland musicians…came looking for a drummer but all my brothers were already out working.” With his mother’s blessing, he joined them on the back of a flatbed in a truck parade, seated on a stack of beer cases:

They had a big bass drum with a light inside that, every time you hit the bass drum, the light came on … It was just the bass drum, the snare drum and the cymbal … They just wanted someone to keep time, somebody to make the big boom.

Carnival also brought out the Black Masking Indians, then called Mardi Gras Indians. Donald Harrison, Sr., who lived just across Chestnut Street from Muhammad in the late 40s and early 50s, started masking with the White Eagles in 1949.

Harrison biographer Al Kennedy noted that Harrison organized Indian practices in the area leading up to Mardi Gras Day, and, according to Jeff Hannusch, “would put on his suit and parade all around the neighborhood.” As Muhmmad recalled, “As a kid I used to follow him and listen at these tambourines and listen at these songs they sang.”

Decades later, Muhammad showed the drummer Stanton Moore how he’d incorporated the Indians’ tambourine patterns into his playing. As Moore wrote:

[Muhammad] got this particular sticking idea by applying the Indians’ main tambourine rhythm to the hi-hat and then filling it in with the left hand. The rhythm that the same RLRR-LRRL sticking spells out with the right hand is similar to what Cubans call the cinquillo.

Muhammad cited the Indians’ influence throughout his career, even in such unlikely places as his hi-hats on the Bob James record “Angela,” familiar to millions as the theme song for the television show “Taxi.”

McDonogh No. 6 and the Hawketts

Donald Harrison, Sr. stayed in a lodge on the grounds of McDonogh No. 6, the elementary school where his father worked as a custodian. Besides bringing Harrison’s tambourine rhythms to his doorstep, the school also provided Muhammad with his first and only formal music teacher.

Solomon Spencer, the music teacher here, taught Muhammad’s older siblings and, according to Muhammad, “everyone in the neighborhood.” He put a drum in Muhammad’s hands on his first day of elementary school, and continued teaching him through middle school and Cohen High School.

“We were taught to read [music] through the school system,” Muhammad said. Mr. Spencer would dismiss anyone from the band who couldn’t read the waltzes and overtures he presented.

By his teens, Muhammad was gigging regularly thanks to another neighborhood connection: Art Neville, whose band the Hawketts rehearsed at his house two blocks away, knocked on Muhammad’s door to recruit him (the band’s previous drummer, John Boudreaux, who’d recorded the local hit “Mardi Gras Mambo” with the group in 1954, left to back “a phony Shirley and Lee.”)

With the Hawketts, Muhammad started playing at Valencia, a private club in the 13th Ward exclusively for white teenagers. “The Valencia Club is where the band got tight and we begin to roll,” Muhammad wrote. Big-name touring artists like Big Joe Turner and Louis Jordan tapped The Hawketts to back them when they played in New Orleans.

In the Studio and on the Road in the 50s and 60s

Muhammad started recording with various artists in the late 1950s, appearing on hits including Larry Williams’ “Short Fat Fannie” and Joe Jones’ “You Talk Too Much” (while some sources list Muhammad as the drummer on Fats Domino’s smash “Blueberry Hill,” that part was more likely played by Tenoo Coleman).

A trip to Dooky Chase Restaurant with Joe Jones in 1958 landed Muhammad a slot in Sam Cooke’s touring band: when Cooke told Jones that he could use a drummer, Jones introduced him to Muhammad, who got the gig by drumming with his hands on a tabletop.

His stint with Cooke helped Muhammad break into the big time (it also introduced him to Dolores “LaLa” Brooks, who would sing lead on The Crystals’ classic “Da Doo Ron Ron,” and whom he would later marry). Landing in Chicago, he became Jerry Butler’s musical director and joined Curtis Mayfield in The Impressions.

After a few years, Muhammad moved to New York, where, as Kalamuu Ya Salaam wrote , he “was one of the main people responsible for transplanting the syncopated sounds from down under to” the city, “and for significantly altering the pulse of contemporary popular music.”

Muhammad became the house drummer for the Apollo Theater. While gigging around town, he wrote, “a lot of the jazz players were starting to check me out because I have this New Orleans thing going on.” As he explained it, “I was able to play the bass drum on the offbeat, where it grooved and it locked in—but it swang.”

He started recording for Blue Note Records, adding his touch to classics like the soul-jazz fusion of Lou Donaldson’s “Alligator Bogaloo” (“That second line beat will make you move,” Muhammad assessed).

Muhammad also took a job creating and performing the drum parts for the original production of the play “Hair” (“The same street beat I heard as a kid in New Orleans, I start playing it with my hands to establish a real tribal sound,” he wrote).

Expanding in jazz and permeating hip hop

Muhammad was a favorite of Roberta Flack, who tapped him to join her band and record her classic “Killing Me Softly.”

After a few years he left to delve deeper into jazz, becoming the house drummer for Prestige Records, and then CTI Records, joining Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter.

Later in the 1970s, Muhammad started recording albums under his own name. “I chose to show a skill of me playing the melody on the drums,” he told Kalamuu Ya Salaam. “When I was living in New Orleans, which is my home, I would hear the guys playing in the street parades. The drummers played the beat but it was along the melody line of the music.”

Starting in the 1980s, some of Muhammad’s drum breaks became go-to samples for hip-hop producers. His playing on Bob James’ “Nautilus,” for example, appeared on tracks by some of the greatest hip hop artists of all time, including Run-DMC, Eric B. & Rakim, the Wu Tang Clan, and A Tribe Called Quest. David Kunian noted that “Everyone from Beck to Tupac sampled his song ‘Crab Apple,’ and ‘Loran’s Dance’ got a second life as the basis for ‘To All The Girls,’ the lead track on the Beastie Boys’ 1989 release ‘Paul’s Boutique.’

Muhammad appreciated his work’s place in hip hop, though by this time he was based in Europe and touring the world with the likes of Sonny Rollins and Ahmad Jamal.

Returning to New Orelans

Beginning in 2002, Muhammad began masking Indian with Big Chief Donald Harrison, Jr., the acclaimed jazz saxophonist and son of Donald Harrison, Sr., whose tambourine playing had entranced Muhammad as a child. Putting on his first Indian suit at 63, he told the Times-Picayune, “I was like a kid having something that he had been wishing for all of his life.”

In 2011 Muhammad reestablished a residence in New Orleans, where he still had family, including members of the Prince of Wales Social Aid and Pleasure Club, which second-lined through the 12th Ward every October. He played occasional shows in town before his death in 2014.

Videos

Clip of a documentary featuring Idris Muhammad discussing his background.

Video posted by cocktailinn.

Clip of a documentary featuring Idris Muhammad discussing his background.

Clip of Idris Muhammad on becoming a session drummer for Blue Note Records after arriving in New York with Sam Cooke.

Video posted by Hudson Music.

Clip of Idris Muhammad on becoming a session drummer for Blue Note Records after arriving in New York with Sam Cooke.

Clip of Idris Muhammad recounting how Art Blakey outfitted him with cymbals.

Video posted by MisterBritt.

Clip of Idris Muhammad recounting how Art Blakey outfitted him with cymbals.

Idris Muhammad performs with Pharaoh Sanders in 1988 (this link is cued to a drum solo within an hour-long concert).

Video posted by milan simich.

Idris Muhammad performs with Pharaoh Sanders in 1988 (this link is cued to a drum solo within an hour-long concert).

"Idris Muhammad: Drum Solo - 2000" from a live performance in Swtizerland.

Video posted by DRUMMERWORLD by Bernhard Castiglioni.

"Idris Muhammad: Drum Solo - 2000" from a live performance in Swtizerland.

Images