Iroquois Theater

413 S. Rampart St.New Orleans LA 70112

Opening in 1912, the Iroquois Theater was one of the first theaters ever to feature jazz in a concert setting. Vaudeville shows, a popular form of stage entertainment in the early 20th century, included everything from comedy to acrobatics, with plenty of music in the mix. According to historians Lynn Abbott and Jack Stewart, that made the venue “a foundry of early blues and jazz activity. From 1913 to the end of the decade, the Iroquois Theater was on the creative front line of distinctively African American entertainment in New Orleans.”

The Iroquois, like most vaudeville theaters, employed a house band to accompany touring artists as well as silent films. In New Orleans, that meant hiring musicians who were fashioning a new style of music, soon to be known as jazz. Their gigs in Storyville cabarets and dance halls loom larger in the popular imagination, but performances in seated theaters are also part of the genre’s complex origin story.

One early headliner at the Iroquois was Butler “String Beans” May. According to Abbott and Doug Seroff, String Beans’ variety act, which included singing and playing piano, made him “the first blues star” in history. He popularized elements of Southern Black vernacular music on stages across the country, including collaborations with New Orleans native Sweetie Matthews May, his one-time wife. (He also inspired Jelly Roll Morton to mount a diamond on one of his front teeth.)

A showcase for future stars

Several locals starred on stage at the Iroquois as well. The most famous today was unknown at the time: Louis Armstrong, who lived two blocks away, won a talent contest here as a youngster, using flour to perform in white face, a reversal of the Black face common in minstrel shows. Author Thomas Brothers notes that Armstrong’s showmanship owed something to the vaudeville performances he took in here.

For a stretch of 1917, the pianist and composer Clarence Williams was a regular at the Iroquois, where he premiered new material. One of New Orleans’ original piano “professors,” Williams was a jazz pioneer who would build a national reputation as a songwriter and music publisher, and became a notable figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

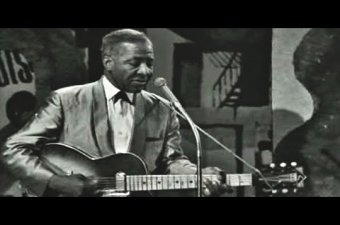

Guitarist Lonnie Johnson played at the Iroquois, along with his brother, the drummer James “Steady Roll” Johnson. They grew up in the area, playing in a family band as teenagers. After cutting his teeth here, Lonnie Johnson became a recording artist in Chicago and New York, producing a catalogue that made him one of the most influential blues guitarists of all time.

One member of the Iroquois’ pit orchestra, 14-year-old Abby “Chinee” Foster, played a drum he built from a banjo head, with sticks whittled from chair rungs. He’d go on to perform with some of the city’s top jazz bands, including the Eagle Band, which was headquartered a few doors down South Rampart Street at the Eagle Saloon.

The proprietor of the Iroquois, Paul Ford, was white, but delegated much of the operation to Black managers (during his run at the Iroquois in 1913, String Beans doubled as stage manager). The theater was among the more respectable nightspots on the outskirts of Black Storyville, a red light district.

Live performances at the Iroquois wound down around 1920, when the 2,000-seat Lyric Theater siphoned audiences into the nearby French Quarter. Billed as “America’s Largest and Finest Colored Theatre,” the Lyric attracted the biggest names in Black vaudeville, and the Iroquois increasingly screened movies (Armstrong recalled paying a nickel to watch “moving pictures” here as a kid).

This building was put to other uses in the mid-20th century, including office space for the United Voters League, which organized New Orleans’ Black electorate here in the early 1960s, before the Voting Rights Act opened its access to the ballot. For decades afterward, the building’s owners, the Meraux estate, left it vacant. Preservationists fought off attempts to demolish it in the 90s, but couldn’t prevent its deterioration.

In 2018 the property was acquired by GBX Group, a developer out of Cleveland that specializes in renovating historical sites. It plans to restore the structure as part of a larger project to revitalize the 400 block of South Rampart Street.

The Iroquois Theater is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Considering it alongside the Little Gem Saloon, the Karnofsky building, and the Eagle Saloon, John Hasse, curator of American Music at the Smithsonian Institution, said “There is probably no other block in America with buildings bearing so much significance to the history of our country’s great art form, jazz.”

Read more about the cultural history of South Rampart Street.

Videos

From author John McCusker: "Louis Armstrong's New Orleans," a look at Satchmo's formative years and the landmarks associated with him, including the Iroquois Theater.

Video by the New Orleans Jazz History Tour company The Cradle of Jazz.

From author John McCusker: "Louis Armstrong's New Orleans," a look at Satchmo's formative years and the landmarks associated with him, including the Iroquois Theater.

New Orleanian Lonnie Johnson, who appeared at the Iroquois in the 1910s, was still performing in the 1960s, when he was hailed as one of the most influential guitarists in blues history.

Video posted by Vintage Video Hub.

New Orleanian Lonnie Johnson, who appeared at the Iroquois in the 1910s, was still performing in the 1960s, when he was hailed as one of the most influential guitarists in blues history.

From August 30, 2021, the day after Hurricane Ida made landfall, a look inside the former Iroquois Theater.

Video by Jordan Hirsch.

From August 30, 2021, the day after Hurricane Ida made landfall, a look inside the former Iroquois Theater.

Images