Magnolia (C.J. Peete) Public Housing Development

2400 Washington AvenueNew Orleans LA 70115

It’s hard to fathom how a single apartment complex contributed as much to American music as the C.J. Peete Public Housing Development did. Hip hop fans everywhere know it as the Magnolia projects, the launching pad of Cash Money Records and home of rap stars Soulja Slim, Juvenile, and Jay Electronica. Its construction in 1939 also led to the establishment of the Dew Drop Inn, a vital hub of the Chitlin Circuit from the 1940s – 60s. Its residents cut countless hit records, and helped sustain New Orleans’ brass band and Black Masking Indian music for generations.

The Magnolia, designated by the city for Black residents only, consisted of low-rise brick buildings arrayed around grassy courtyards, eventually sprawling to include 1,400 apartments.

When the Housing Authority of New Orleans bulldozed several square blocks to build the Magnolia, Frank Painia had to move his barbershop from its footprint. He then opened the Dew Drop Inn across the street, selling food and drinks to the workers building the complex. When he expanded and added live music in 1945, the Dew Drop quickly attracted the nation’s top Black performers. More than a performance venue, it was a nationally renowned artistic hotbed and community center that catalyzed the birth of rock and roll.

Music from the Dew Drop was audible in the Magnolia and inspired budding artists there, including saxophonist Harold Battiste and pianist Edward Frank. Each emerged as a leader in the modern jazz movement in New Orleans while earning a national reputation by playing and arranging rhythm and blues.

Battiste was the mastermind behind New Orleans’ AFO Records, a pioneering record label owned collectively by the Black musicians who made its music, including Barbara George’s 1961 smash “I Know.” He then arranged chart-toppers for Sam Cooke and Sonny and Cher, and helped Malcolm Rebennack break out by adopting the persona of Dr. John. A celebrated producer and composer, Battiste later became one of New Orleans’ great jazz educators as well.

Frank, a bebop enthusiast in the late 1940s, hosted all-day jam sessions at his home in the Magnolia with like-minded modernists. At 23 a ruptured blood vessel partially paralyzed his left arm, but he earned a spot in bandleader Dave Bartholomew’s elite group while playing with one hand. Around 1956 Frank became a regular in Cosimo Matassa’s legendary studio band, waxing scores of R&B hits including Shirley and Lee’s “Let the Good Times Roll.”

When Frank played his piano at home, a kid who lived in a nearby apartment, Raymond Jones, came around for lessons. Frank obliged, and Jones became known as Ray J, an in-demand local bandleader and arranger, and longtime band director at Xavier Prep High School. Ray J also performed with bassist Bill Sinigal, a fellow Magnolia resident and veteran of the Dew Drop house band, who recorded the Mardi Gras classic “Second Line” with his group the Skyliners in 1964.

A Wellspring for Hip Hop

Charles Leach grew up in the Magnolia in the 1960s, and spun records at block parties in its courtyards in the 80s as DJ Captain Charles. He nurtured the rise of hip hop in New Orleans by breaking a number of early local rap and bounce records in area clubs.

A young teen in the Magnolia, James Tapp, starting rapping as Magnolia Slim in 1993 and went national as Soulja Slim with No Limit Records in 1995, offering unflinching tales of the drug trade that had grown in the complex in those years. Slim was murdered in 2003, on the verge of his greatest success, the hit “Slow Motion,” a collaboration with Juvenile, another rapper from the Magnolia (it went No. 1 posthumously).

Juvenile, born Terius Gray, was one of Cash Money Records’ Hot Boys, along with fellow Magnolia resident Turk; B.G., who lived nearby, and Lil Wayne. Brothers Bryan “Birdman” Williams and Ronald “Slim” Williams founded Cash Money, one of the most successful labels in hip-hop, in the Magnolia, and the complex was part of their brand. The Hot Boys were “neighborhood superstars” who rapped about living large while staying connected to the streets they came from. The Magnolia was name-checked often, and the setting for several popular videos, including one for Juvenile’s 1998 hit “Ha.”

When the levees failed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005 parts of the Magnolia flooded, though its brick buildings were structurally sound. In 2007 the New Orleans City Council voted to demolish the complex, part of a larger agenda of the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development to decentralize subsidized housing. The result was the displacement of a multi-generational community.

The Magnolia’s legacy in hip hop continued, though, thanks to former residents including Magnolia Shorty, Keedy Black, Vockah Redu, and G.I. Peachez, the sister of Soulja Slim, who represented it in the post-Katrina years. There was even another breakout star: Jay Electronica, who grew up in the Magnolia, left New Orleans in 1996 and, in the late 2000s, emerged as an A-list lyricist. His Grammy-nominated 2021 album A Written Testimony included a collaboration with Jay-Z called “Ghost of Soulja Slim.”

While artists from the Magnolia reached the height of success, the community’s musical life went beyond the recording industry. The complex was at the intersection of Washington Avenue and LaSalle Streets and across from A.L. Davis Park, a longstanding second line route and rendezvous point for Black Masking Indians, taproots of the city’s culture since the 1800s. Many social aid and pleasure club members and Indians—including, aptly, members of the Wild Magnolias—lived in the development. The Original Lady Buckjumpers, led by Linda Tapp Porter, the mother of Soulja Slim, continue to parade through the new mixed-income development here, called Harmony Oaks, to celebrate their history.

Read more about the role of public housing in the development of New Orleans music.

Videos

"Enter the Magnolia: The Story of the C.J. Peete Housing Projects" 35-minute documentary by Newtral Groundz from 2020.

Video by Newtral Groudz.

"Enter the Magnolia: The Story of the C.J. Peete Housing Projects" 35-minute documentary by Newtral Groundz from 2020.

The video for Juvenile's hit "Ha" shows the Magnolia in 1998, putting it on the map for hip hop fans across the country.

Video from Cash Money/Universal Motown Records.

The video for Juvenile's hit "Ha" shows the Magnolia in 1998, putting it on the map for hip hop fans across the country.

The video for "Nolia Clap," which charted nationally in 2004, was filmed in its namesake Magnolia public housing development.

Video from Rap-A-Lot Records.

The video for "Nolia Clap," which charted nationally in 2004, was filmed in its namesake Magnolia public housing development.

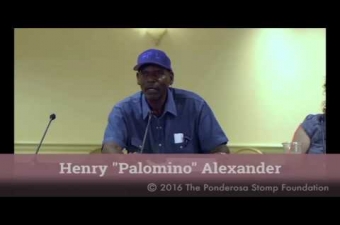

Clips from the 2011 Ponderosa Stomp Conference panel “Booty Green: Reflections on Bobby Marchan” on Marchan and the origins of Cash Money Records.

Video copyright owned by The Ponderosa Stomp Foundation and cannot be used by 3rd party without written permission from the Ponderosa Stomp Foundation. Learn more: http://www.PonderosaStomp.com.

Clips from the 2011 Ponderosa Stomp Conference panel “Booty Green: Reflections on Bobby Marchan” on Marchan and the origins of Cash Money Records.

Images